The message, broadcast in an internal video to the 60,000-strong federal agency, was clear: The Transportation Security Administration had an integrity problem, not to mention a public relations headache.

Against the lavender-hued backdrop of the Homeland Security Department logo, then-Deputy Administrator John Halinski announced that employee misconduct and criminal behavior – along with the headlines those misdeeds spurred – were “damaging to the mission and to our reputation as a high-performance counterterrorism agency.”

“Folks, we’re better than this. We can do better than this,” Halinksi said in the recorded announcement, which was required viewing for the agency’s workforce. “Illegal activity of any kind will not be tolerated, and supervisors must lead by example.”

Released months after a House hearing during which lawmakers grilled TSA officials about misconduct, the 2013 video outlined a strategy to target corruption, which was on the rise. From 2010 to 2012, the TSA investigated 9,600 misconduct cases, nearly half of which merited the employee being suspended or fired, according to a 2013 U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

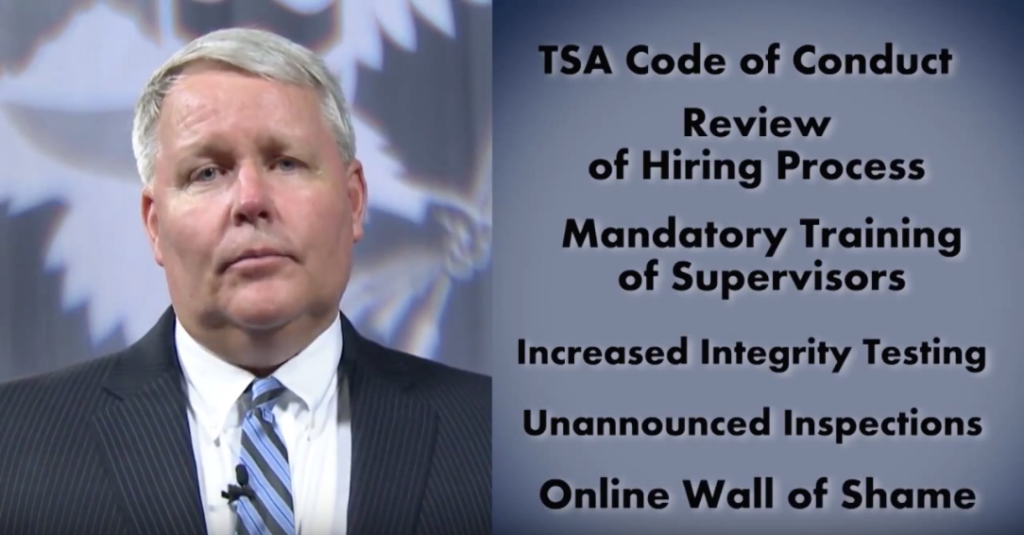

Halinski’s plan included training supervisors about employee conduct and accountability, staging unannounced airport inspections and creating an online wall of shame to discourage misconduct.

But whistleblower complaints, internal memos, a recently filed lawsuit and interviews with more than 40 current and former TSA employees show that the agency’s upper tiers did not always take his message to heart.

Halinski left the agency in July 2014, less than a year after he broadcast that message. By then, the TSA was under a cloud of suspicion and reeling over controversial gun purchases that had embroiled at least two employees, including the then-director of the Federal Air Marshal Service, and drew attention from Congress.

Before he left, Halinski signed off on what several current and former TSA employees call an unusual 28.75 percent salary increase alongside a noncompetitive promotion for an executive assistant.

Current and former officials say that at a minimum, the promotion and subsequent raise strained ethical boundaries because it went far beyond the normal range of 3 to 5 percent salary bumps, according to internal documents obtained by Reveal.

The questionable move and resulting resentment highlight the internal dysfunction, distraction and distrust that have racked the agency’s senior ranks for years. The complaints also underscore how disconnected some middle managers and the rank and file feel, as evidenced by consistently low morale.

Current and former officials say a double standard exists for senior leaders and promotes a “shut up and move up” culture within the oft-maligned agency.

Robert Cammaroto, a retired senior official who joined the TSA at its inception, said the harried effort to create the agency after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks permitted an unhealthy culture to develop – and fester.

Those who resisted or spoke out about concerns ranging from security gaps to personnel moves say they were muzzled, pushed aside or forced out, depleting the number of experienced managers or causing upheaval in parts of the agency. That has left the current administrator, Peter Neffenger, with the difficult task of cleaning up the agency’s image and lingering integrity issues, real or perceived.

The cultural issues are partly due to a mishmash of personnel from the military, law enforcement and the aviation industry, different factions of which often battled for power. Some were more focused on career advancement than the mission, Cammaroto said.

Instead of dealing with misconduct, such behavior often was buried, as that was considered “the best thing for the organization.” One senior leader after another was allowed to resign rather than face discipline, while lower-level employees were punished or fired, he said.

“Because there were rules that were a little less stringent in the race to stand up the agency in the post-9/11 fever, a lot of things – hiring, promotions, acquisitions – got bent and have never gotten straightened out,” Cammaroto said. “It became kind of a food fight for survival and to move ahead.”

Current and former employees echo those descriptions, adding that top officials reward one another, including automatic bonuses to senior managers who make more than $160,000 a year.

In one recently reported example, a top official who oversaw the office responsible for airport screeners was given cash bonuses and awards that reached nearly $100,000, despite exposed security failures on his watch. That official kept his job.

Other misconduct allegations include:

- Joseph Salvator, who until recently led the TSA’s intelligence and analysis office, had several complaints against him, including three charges of lack of candor sustained by an internal investigation, according to a whistleblower complaint. But instead of being fired, as recommended, Salvator was demoted. Lack of candor is a common reason for a federal employee to be terminated.

- Salvator and his predecessor as head of intelligence, Stephen Sadler, are among those named in a discrimination lawsuit against the Homeland Security Department by another senior-level TSA employee. In the lawsuit, a former deputy alleges that he faced retaliatory discrimination after he refused to cover up sexual harassment and discrimination by Salvator and others. The TSA declined to comment on the pending litigation.

- The chief of the agency’s inspections office, which handles internal affairs matters and once was led temporarily by Salvator, is herself under scrutiny for an alleged hostile work environment and is the focus of several discrimination complaints, according to current and former employees. Sophia Jones has been in that role since February 2015. TSA officials declined to comment because the investigation is still open.

- Under Halinski’s direction, the executive assistant who received the 28.75 percent pay raise also attended a federal law enforcement academy to learn how to be a criminal investigator. On assignment from the Federal Air Marshal Service, a subagency of the TSA, she was the sole participant in a pilot program that ended with her graduation.

Congressional investigators have heard those allegations and more, according to current and former TSA employees who have spoken recently to lawmakers or their aides. In what has practically become an annual tradition of investigating the TSA, two House committees have launched probes into how the agency handles misconduct. U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., separately requested that government auditors review the agency’s acquisition practices.

The House Oversight and Government Reform Committee also held a hearing last year, spurred by a Reveal report, that addressed allegations of misconduct by federal air marshals. Air marshals were arrested 148 times from November 2002 through February 2012, according to a recent ProPublica report. Aides for both the House oversight and homeland security committees declined to comment on the ongoing investigations.

In a written response to questions from Reveal, a senior TSA official said Neffenger has set expectations that TSA employees be models of ethical behavior, adding that the agency does not tolerate illegal, unethical or immoral conduct, regardless of seniority or position.

The senior TSA official wrote that the agency took “appropriate action … in accordance with policy” regarding the allegations and discipline against Salvator, who now holds a high-level position in the agency’s Office of Security Operations. The woman promoted by the former deputy administrator took a position in the agency’s intelligence office with “a raise commensurate to the added responsibilities and training,” the official wrote.

The agency had little to say about Halinski, other than that he retired in 2014 after decades of public service. In an interview, Halinski defended his record on improving integrity within the TSA, saying he aimed to hold those accountable when misconduct was substantiated.

He denied that he or Robert Bray, the former air marshals director, retired because of the gun-buying investigation, as both already had said they intended to leave their jobs. He said disgruntled air marshals who were “slinging mud” stirred up the controversy because they were upset over plans to close six field offices.

As far as the young female air marshal he promoted, Halinski said he gave all his executive assistants a choice in their next job – and a 3 percent pay raise.

He said he wanted to balance out the woman’s salary after she chose to work in intelligence and, as a result, would lose additional law enforcement pay. Air marshals had caused such a firestorm about the pilot program to cross-train them as criminal investigators that Halinski said he decided to shut it down.

“I didn’t have time to put up with folks complaining about it,” said Halinski, who now works in the private sector. “I follow the book. I don’t create my own rules.”

The same went for personnel decisions, Halinski said, which he made based on what was best for the agency, not preferential treatment or out of retaliation. He acknowledged that he wasn’t always popular as a result and faced at least one inspector general’s inquiry, which he said cleared him of any wrongdoing.

The inspector general’s office reported that it could not substantiate allegations of discrimination, favoritism and abuse of power, but it acknowledged that there was a perception among some employees that those issues existed.

Under Halinski, the agency went through an internal realignment that paralleled slashed budgets and his push to expand the agency. Yet several high-ranking officials around the country say they were pushed to retire or resign through so-called directed reassignments.

A fast-ascending senior executive who once ran the agency’s national field operations, Heather Callahan Chuck, said top leaders flung her from one position to another after she raised red flags about a host of security problems and other issues in Hawaii.

Soon after her arrival in Honolulu in early 2014, Chuck raised concerns to her supervisors, who in turn blamed her for the problems. She then was reassigned or given temporary assignments several times.

Chuck, who filed a discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, eventually decided to resign in February 2015, one of at least two dozen senior officials to quit when faced with a forced move, she said. The TSA late last month implemented an additional layer of review before approving such reassignments.

“When you take experience away from that equation, when you take people away from the mission, you are impacting security,” Chuck said. “The agency has stated core values of integrity, innovation and teamwork, but that’s not how they act. There’s a total lack of integrity.”

John Pistole, who served as the TSA administrator from 2010 until late 2014, declined to comment on specific personnel matters, citing privacy concerns. He said the agency made progress regarding integrity issues during his tenure, but there still was work to do.

Arriving at the TSA after a career with the FBI, Pistole immediately launched the Office of Professional Responsibility, he said. He did that to professionalize the agency and establish uniform discipline and punishment, which were not consistently meted out by the more than 100 security directors who oversaw TSA operations at 450 airports nationwide.

Pistole said he told leadership that they needed to model hard work, professionalism and integrity. Some people agreed to that, he said, and some did not.

“I was disappointed that time and time again, we would have things come to light,” he said, which raised questions about the agency’s culture, hiring and training practices – and its supervisors. “I had a clear expectation of senior leaders: If you’re aware of misconduct by anyone, you need to act immediately. It’s not only perilous for you not to do so, but it can be a black eye for the agency.”

While misconduct allegations reach across the TSA, one office that offers a window into the agency’s woes is its intelligence and analysis division. Buffeted by turnover at the top, the office has become a stage for finger-pointing, allegations of misconduct and leadership struggles. That has become manifest in investigations, discrimination complaints and the recent lawsuit.

Much of the spotlight now focuses on Salvator, an ex-Marine who reached several high-ranking roles, including turns in the intelligence, security operations and inspections offices. The intelligence office’s former No. 2, Mark Livingston, alleges in a lawsuit filed last month in U.S. District Court in Maryland that he faced discrimination after he stood up to Salvator and others.

According to the lawsuit, Salvator leered at Livingston’s female executive assistant in a sexually suggestive manner in June 2014. Then a deputy assistant administrator in another office, Salvator later confronted Livingston about the exchange, saying it was “our word against her if she files a complaint.” When Livingston, a disabled veteran, said he would tell the truth if asked, Salvator allegedly said he could not work with Livingston if he was a “Boy Scout” and made other threats. Livingston was reassigned months later.

“The harassment and retaliation that Mark Livingston and females on his staff … experienced at TSA reflects a hostile ‘old boys’ club’ environment and tolerance for sex discrimination in the workplace, which simply must end,” Livingston’s attorney, Tamara Miller, said in a statement to Reveal.

Livingston’s assistant, Alyssa Bermudez (formerly Jackson), filed a complaint about another TSA official with the Office of Inspections, which now was led by Salvator. A newly hired combat veteran, Bermudez had been on the job for about a month when the incident with Salvator had occurred. Bermudez said she received high performance scores on her evaluations. But that didn’t ensure her a job. As a probationary employee with less than a year on the job, she could be fired with little, if any, recourse.

Around the same time as Livingston’s reassignment, the Salvator-led inspections office deemed Bermudez’s complaint unfounded, in October 2014.

“I trusted in senior leaders within the agency to take my sexual harassment complaint seriously,” she said in a written statement. “I was treated not as a victim, but as a traitor whose complaint threatened the organization.”

In November 2014, the intelligence division learned that Salvator was selected to take over its office at a town hall meeting. At that meeting, Bermudez asked why Livingston had been removed.

The next day – the day before Thanksgiving – Bermudez was placed on administrative leave for 30 days. When she returned to work in early 2015, she immediately was reassigned. Months later, five days before her one-year probationary period was to end, she was fired. Through a TSA spokesman, Salvator declined to comment.

Source: https://revealnews.org/article/besieged-by-misconduct-tsa-sows-culture-of-dysfunction-and-distrust/